Atlanta Georgian

August 14th, 1913

By JAMES B. NEVIN.

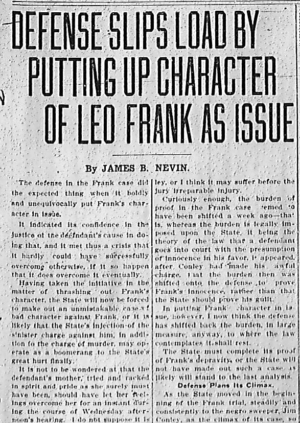

The defense in the Frank case did the expected thing when it boldly and unequivocally put Frank's character in issue.

It indicated its confidence in the justice of the defendant's cause in doing that, and it met thus a crisis that it hardly could have successfully overcome otherwise, if it so happen that it does overcome it eventually.

Having taken the initiative in the matter of thrashing out Frank's character, the State will now be forced to make out an unmistakable case of bad character against Frank, or it is likely that the State's injection of the sinister charge against him, in addition to the charge of murder, may operate as a boomerang to the State's great hurt finally.

It is not to be wondered at that the defendant's mother, tried and racked in spirit and pride as she surely must have been, should have let her feelings overcome her for an instant during the course of Wednesday afternoon's hearing. I do not suppose it is even remotely possible for any person not a mother to understand all she has gone through.

Her vehement protest against the vile things being said and hinted about her boy—true or untrue, though such things always are untrue in mother love, I take it—serves to illustrate, however, how very vital to the defense now is the establishing of Frank's good character.

I doubt that anything thus far said to the jury has so profoundly impressed it as the unspeakable thing Conley said of the defendant. The jury is only human, and it can no more dodge impressions than other people can.

Impression Must Be Erased.

The defense is up against the herculean task of removing all of that impression from the mind of the jury—the twelve minds of the jury, indeed—for it will not do to leave even a fraction of Conley's story undemolished!

Manifestly, therefore, the defense could not, if it would get away altogether from the matter of Frank's character. It found itself necessarily forced to the other extreme of the situation set up by the State.

The State, on the other hand, by reason of the defense's challenging attitude in the matter of forcing the issue of Frank's character, must now corroborate the frightful story of Conley, or I think it may suffer before the jury irreparable injury.

Curiously enough, the burden of proof in the Frank case seemed to have been shifted a week ago—that is, whereas the burden is legally imposed upon the State, it being the theory of the law that a defendant goes into court with the presumption of innocence in his favor, it appeared, after Conley had made his awful charge, that the burden then was shifted onto the defense to prove Frank's innocence, rather than that the State should prove his guilt.

In putting Frank's character in issue, however, I now think the defense has shifted back the burden, in large measure, anyway, to where the law contemplates it shall rest.

The State must complete its proof of Frank's depravity, or the State will not have made out such a case is likely will stand to the last analysis.

Defense Plans Its Climax.

As the State moved in the beginning of the Frank trial, steadily and consistently to the negro sweeper, Jim Conley, as the climax of its case, so to-day the defense is moving, every bit as steadily and as persistently, to the defendant, Leo Frank, as the climax of its case.

The State's case progressed ever up to Conley—the defense's case is progressing ever up to Frank.

It is Conley vs. Frank no less than it is the State vs. Frank.

No intelligent and discriminating observer, abreast with the status of the trial doubts that, or has doubted it for days.

Either Leo Frank's life will answer for Mary Phagan's, or Jim Conley's will!

The capstone of the defense undoubtedly will be the defendant's statement. He will make it just before the defense rests its pleading.

Already, this anticipated dramatic event has cast its shadow before. The public is looking forward to Frank's personal statement with no less keen interest than it looked forward, perhaps, to the terrible story of Conley.

Frank will be permitted, under the law, to make a statement to the jury, but without being permitted to swear to its truthfulness. The jury will be instructed that it may accept that statement, if it so elects, in preference to all the sworn testimony in the case; or it may accept it in part and reject it in part; or it may reject it altogether.

The jury alone and finally is made the sole judge of the defendant's credibility on the stand.

Tells What He Pleases.

The defendant can not be impeached; he can not be cross-examined; he can not be prompted by his attorneys. He simply states what he pleases, in the exact way he pleases, and in such detail or lack of detail as he pleases. It is strictly a matter between the defendant and the jury.

Leo Frank is one of the few defendants in murder cases coming under my observation, who absolutely refrained from discussing his case, in any phase of it, in advance of his trial.

Only at the Coroner's inquest, where he as obliged to talk, had he opened his lips to speak concerning the charge brought against him. In adopting this course, he unquestionably was well within his legal rights, and well within the bounds of common sense, too, no doubt, but the fact remains that the course he pursued is the unusual one.

I said in a former article that Frank apparently is a very patient man—and such men fight mighty hard when once aroused—and the more I reflect upon that observation, the more I am inclined to emphasize it.

He has waited four months to tell his story—but when he does it, it will be related in the proper presence, the court and the jury.

It is unlikely that the public wishes to hear anything quite so much as exactly what Frank himself has to say of the charges lodged against him.

It has heard what everybody else both intimately and distantly concerned, has had to say. It has heard Conley's story from Conley's own lips—but thus far Frank has been as silent as the grave of the dead girl itself!

It is impossible to forecast the effect, of Frank's statement upon the jury. It may have as powerful an effect in clearing him as Conley's horrible statement surely must have had by way of then condemning him.

Juries Have Accepted It.

I have seen cases in which the defendant's statement alone evidently served to clear him. I have known juries to accept it as the truth, over and above all the sworn testimony—just as the jury has the unquestioned right to do.

On the other hand, I have seen the defendant's statement fall flat and stale. I have seen it have no more effect upon the jury than rain has upon a duck's back.

It all depends upon the defendant's manner and bearing on the stand, the seeming sincerity of his recital, its plausibility and probability, the character of the man making it, his intelligence and apparent directness of purpose, the necessity of the statement as bearing alone and entirely upon weak points in either his own or the State's case, and many other things.

The defendant's statement presumably dovetails, of course, into the case as lawyers therefore have made out—and yet I have known the defense to introduce the defendant the first thing and proceed thereafter to the building of a case around his statement.

As this case is so thoroughly a fight between Conley and Frank—that is, between Conley's evidence and Frank's evidence—it will be intensely interesting to watch and see how eventually the jury views the relative value of both.

Much Rests on Defendant.

Conley's story, as amazing and as shocking as it is in parts, nevertheless has been accepted by many as the truth. Presumably those people who already have made up their minds still are willing to be convinced — as violent as the presumption may be in some cases — if Frank can convince them.

Upon Frank's statement, therefore, it is entirely possible the entire case may turn finally.

To discredit Frank's statement, to be sure, will be his heavy self-interest and the fact that it is not upon oath and not subject to cross-examination.

To discredit Conley's story, however, is his also heavy self-interest and the fact that, while his story was delivered on oath, his character admittedly is very bad and his numerous previous sworn statements admittedly false in many important details.

The situation thus set up is about as pretty as it could be, from an abstract legal standpoint. If it were a surgical problem we were considering, I should predict that the operation will be beautiful and brilliant in any event—but as for the patient—well, I really could not say!

* * *

- 001 Monday, 28th April 1913 10,000 Throng Morgue to See Body of Victim [Last Updated On: May 7th, 2025] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 002 Monday, 28th April 1913 12-Year-Old Girl Sobs Her Love for Slain Child [Last Updated On: May 7th, 2025] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 003 Monday, 28th April 1913 3 Youths Seen Leading Along a Reeling Girl [Last Updated On: February 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 004 Monday, 28th April 1913 Arrested as Girl’s Slayer [Last Updated On: February 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 005 Monday, 28th April 1913 Body Dragged by Deadly Cord After Terrific Fight [Last Updated On: February 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 006 Monday, 28th April 1913 Chief and Sleuths Trace Steps in Slaying of Girl [Last Updated On: February 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 007 Monday, 28th April 1913 City Chemist Tests Stains For Blood [Last Updated On: February 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 008 Monday, 28th April 1913 Gantt Was Infatuated With Girl; at Factory Saturday [Last Updated On: February 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 009 Monday, 28th April 1913 Girl and His Landlady Defend Mullinax [Last Updated On: February 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 010 Monday, 28th April 1913 Girl to Be Buried in Marietta To-morrow [Last Updated On: February 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 011 Monday, 28th April 1913 Girl’s Grandfather Vows Vengeance [Last Updated On: February 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 012 Monday, 28th April 1913 Horrible Mistake, Pleads Mullinax, Denying Crime [Last Updated On: February 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 013 Monday, 28th April 1913 “I Could Trust Mary Anywhere,” Her Weeping Mother Says [Last Updated On: February 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 014 Monday, 28th April 1913 Incoherent Notes Add to Mystery in Strangling Case [Last Updated On: February 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 015 Monday, 28th April 1913 Lifelong Friend Saw Girl and Man After Midnight [Last Updated On: February 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 016 Monday, 28th April 1913 Look for Negro to Break Down [Last Updated On: February 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 017 Monday, 28th April 1913 Mullinax Blundered in Statement, Say Police [Last Updated On: February 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 018 Monday, 28th April 1913 Negro is Not Guilty, Says Factory Head [Last Updated On: February 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 019 Monday, 28th April 1913 Neighbors of Slain Girl Cry for Vengeance [Last Updated On: February 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 020 Monday, 28th April 1913 Pinkertons Take Up Hunt for Slayer [Last Updated On: February 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 021 Monday, 28th April 1913 Playful Girl With Not a Bad Thought [Last Updated On: February 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 022 Monday, 28th April 1913 Police Question Factory Superintendent, The Atlanta Georgian [Last Updated On: May 7th, 2025] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 023 Monday, 28th April 1913 Slain Girl Modest and Quiet, He Says [Last Updated On: February 21st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 024 Monday, 28th April 1913 Soda Clerk Sought in Phagan Mystery [Last Updated On: February 21st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 025 Monday, 28th April 1913 Story of the Killing as the Meager Facts Reveal It [Last Updated On: May 7th, 2025] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 026 Monday, 28th April 1913 Suspect Gantt Tells His Own Story [Last Updated On: February 21st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 027 Monday, 28th April 1913 Where and With Whom Was Mary Phagan Before End? [Last Updated On: April 29th, 2025] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 028 Tuesday, April 29, 1913 Bartender Confirms Gantt's Statement, Atlanta Georgian [Last Updated On: May 7th, 2025] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 029 Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Charge is Basest of Lies, Declares Gantt [Last Updated On: February 21st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 030 Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Factory Employee May Be Taken Any Moment, Atlanta Georgian [Last Updated On: May 14th, 2025] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 031 Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Factory Head Frank and Watchman Newt Lee are Sweated by Police [Last Updated On: February 21st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 032 Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Former Play mates Meet Girl’s Body at Marietta [Last Updated On: May 20th, 2025] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 033 Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Guilt Will Be Fixed Detectives Declare [Last Updated On: February 21st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 034 Tuesday, 29th April 1913 I Feel as Though I Could Die, Sobs Mary Phagan's Grief-Stricken Sister [Last Updated On: May 21st, 2025] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 035 Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Is the Guilty Man Among Those Held? [Last Updated On: February 21st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 036 Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Keeper of Rooming House Enters Case [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 037 Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Loyalty Sends Girl to Defend Mullinax [Last Updated On: May 29th, 2025] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 038 Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Negro Watchman is Accused by Slain Girl’s Stepfather [Last Updated On: May 29th, 2025] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 039 Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Nude Dancers Pictures Upon Factory Walls [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 040 Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Pastor Prays for Justice at Girls Funeral [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 041 Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Seek Clew in Queer Words in Odd Notes [Last Updated On: June 10th, 2025] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 042 Tuesday, 29th April 1913 Slayers Hand Print Left On Arm Of Girl [Last Updated On: June 10th, 2025] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 043 Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Boy Sweetheart Says Girl Was to Meet Him Saturday [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 044 Wednesday, 30th April 1913 City Offers $1,000 as Phagan Case Reward [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 045 Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Clock Misses Add Mystery to Phagan Case [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 046 Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Confirms Lee’s Story of Shirt [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 047 Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Girl’s Death Laid to Factory Evils [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 048 Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Great Crowd at Phagan Inquest [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 049 Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Handwriting of Notes is Identified as Newt Lees [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 050 Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Leo Frank’s Friends Denounce Detention [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 051 Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Looks Like Frank is Trying to Put Crime on Me, Says Lee [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 052 Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Machinist Tells of Hair Found in Factory Lathe [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 053 Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Mother Prays That Son May Be Released [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 054 Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Net Closing About Lee, Says Lanford [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 055 Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Newt Lee on Stand at Inquest Tells His Side of Phagan Case [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 056 Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Newt Lees Testimony as He Gave It at the Inquest [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 057 Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Policeman Says Body Was Dragged From Elevator [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 058 Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Reward of $1,000 Urged by Mayor [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 059 Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Sergeant Brown Tells His Story of Finding of Body [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 060 Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Sisters New Story Likely to Clear Gantt as Suspect [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 061 Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Tells Jury He Saw Girl and Mullinax Together [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 062 Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Tells of Watchman Lee Explaining the Notes [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 063 Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Went Down Scuttle Hole on Ladder to Reach Body [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 064 Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Witness Saw Slain Girl and Man at Factory Door [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 065 Wednesday, 30th April 1913 Writing Test Points to Negro [Last Updated On: March 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 066 Thursday, 1st May 1913 State Enters Phagan Case; Frank and Lee are Taken to Tower [Last Updated On: March 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 067 Thursday, 1st May 1913 Terminal Official Certain He Saw Girl [Last Updated On: March 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 068 Friday, 2nd May 1913 Dorsey Puts Own Sleuths Onto Phagan Slaying Case [Last Updated On: March 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 069 Friday, 2nd May 1913 Police Still Puzzled by Mystery of Phagan Case [Last Updated On: March 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 070 Saturday, 3rd May 1913 Analysis of Blood Stains May Solve Phagan Mystery [Last Updated On: March 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 071 Sunday, 4th May 1913 Dr. John E. White Writes on the Phagan Case [Last Updated On: March 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 072 Sunday, 4th May 1913 Gov. Brown on the Phagan Case [Last Updated On: March 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 073 Sunday, 4th May 1913 Grand Jury to Take Up Phagan Case To-morrow [Last Updated On: March 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 074 Sunday, 4th May 1913 Old Police Reporter Analyzes Mystery Phagan Case Solution Far Off, He Says [Last Updated On: March 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 075 Sunday, 4th May 1913 Slayer of Mary Phagan May Still be at Large [Last Updated On: March 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 076 Monday, 5th May 1913 Coroners Jury Likely to Hold Both Prisoners [Last Updated On: March 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 077 Monday, 5th May 1913 Crowds at Phagan Inquest [Last Updated On: March 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 078 Monday, 5th May 1913 Frank on Witness Stand [Last Updated On: March 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 079 Monday, 5th May 1913 Judge Charges Grand Jury to Go Deeply Into Phagan Mystery [Last Updated On: March 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 080 Monday, 5th May 1913 Judge W. D. Ellis Charges Grand Jury to Probe into Phagan Slaying Mystery [Last Updated On: March 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 081 Monday, 5th May 1913 Phagan Girl’s Body Exhumed [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 082 Tuesday, 6th May 1913 Bowen Still Held by Houston Police in the Phagan Case [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 083 Tuesday, 6th May 1913 Brother Declares Bowen Left Georgia in August [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 084 Tuesday, 6th May 1913 Frank’s Testimony Fails to Lift Veil of Mystery [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 085 Tuesday, 6th May 1913 How Frank Spent Day of Tragedy [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 086 Tuesday, 6th May 1913 Newest Clews in Phagan Case Not Yet Public [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 087 Tuesday, 6th May 1913 Phagan Case and the Solicitor Generals Power Under Law—Dorsey Hasnt Encroached on Coroner [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 088 Wednesday, 7th May 1913 Employee of Lunch Stand Near Pencil Factory is Trailed to Alabama [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 089 Wednesday, 7th May 1913 Lee is Quizzed by Dorsey for New Evidence [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 090 Wednesday, 7th May 1913 Phagan Girls Body Again Exhumed for Finger-Print Clews [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 091 Wednesday, 7th May 1913 Solicitor Dorsey Orders Body Exhumed in the Hope of Getting New Evidence [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 092 Thursday, 8th May 1913 Another Clew in Phagan Case is Worthless [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 093 Thursday, 8th May 1913 Black Testifies Quinn Denied Visiting Factory [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 094 Thursday, 8th May 1913 Boots Rogers Tells How Body Was Found [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 095 Thursday, 8th May 1913 Didnt See Girl Late Saturday, He Admits [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 096 Thursday, 8th May 1913 Frank Answers Questions Nervously When Recalled [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 097 Thursday, 8th May 1913 Frank of Nervous Nature; Says Superintendent Aide [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 098 Thursday, 8th May 1913 Girl Employe on Fourth Floor of Factory Saturday [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 099 Thursday, 8th May 1913 Grand Jury to Sift the Evidence in the Phagan Case Within the Next Few Days [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 100 Thursday, 8th May 1913 Inquest Scene is Dramatic in its Tenseness [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 101 Thursday, 8th May 1913 Lee Repeats His Private Conversation With Frank [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 102 Thursday, 8th May 1913 Leo Frank is Again Quizzed by Coroner [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 103 Thursday, 8th May 1913 Pinkerton Detective Tells of Call From Factory Head [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 104 Thursday, 8th May 1913 Police Still Withhold Evidence. Frank To Be Examined on New Lines [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 105 Thursday, 8th May 1913 Quinn, Foreman Over Slain Girl, Tells of Seeing Frank [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 106 Thursday, 8th May 1913 Stenographer in Factory Office on Witness Stand [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 107 Friday, 9th May 1913 Best Detective in America Now is on Case, Says Dorsey [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 108 Saturday, 10th May 1913 Guard of Secrecy is Thrown About Phagan Search by Solicitor [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 109 Sunday, 11th May 1913 Caught Frank With Girl in Park, He Says [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 110 Sunday, 11th May 1913 Frank is Awaiting Action of the Grand Jury Calmly [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 111 Sunday, 11th May 1913 Mary Phagans Death Only Assured Fact Developed [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 112 Sunday, 11th May 1913 Weak Evidence Against Men in Phagan Slaying [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 113 Monday, 12th May 1913 Burns Called into Phagan Mystery; On Way From Europe [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 114 Monday, 12th May 1913 Phagan Case is Delayed [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 115 Tuesday, 13th May 1913 Frank’s Life in Tower [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 116 Tuesday, 13th May 1913 Mother Thinks Police Are Doing Their Best [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 117 Tuesday, 13th May 1913 New Theory is Offered in Phagan Mystery [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 118 Wednesday, 14th May 1913 Friends Say Franks Actions Point to Innocence [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 119 Wednesday, 14th May 1913 Secret Hunt by Burns in Mystery is Likely [Last Updated On: March 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 120 Thursday, 15th May 1913 Burns Investigator Will Probe Slaying [Last Updated On: April 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 121 Friday, 16th May 1913 $1,000 Offered Burns to Take Phagan Case [Last Updated On: April 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 122 Friday, 16th May 1913 Burns Hunt for Phagan Slayer Begun [Last Updated On: April 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 123 Friday, 16th May 1913 Secret Probe Began by Burns Agent into the Phagan Mystery [Last Updated On: April 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 124 Saturday, 17th May 1913 New Phagan Witnesses Have Been Found [Last Updated On: April 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 125 Sunday, 18th May 1913 Burns, Called in as Last Resort, Faces Cold Trail in Baffling Phagan Case [Last Updated On: April 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 126 Sunday, 18th May 1913 Burns Sleuth Makes Report in Phagan Case [Last Updated On: April 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 127 Sunday, 18th May 1913 Greeks Add to Fund to Solve Phagan Case [Last Updated On: April 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 128 Monday, 19th May 1913 Burns Agent Outlines Phagan Theory [Last Updated On: April 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 129 Monday, 19th May 1913 Burns Eager to Solve Phagan Case [Last Updated On: April 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 130 Tuesday, 20th May 1913 Cases Ready Against Lee and Leo Frank [Last Updated On: April 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 131 Wednesday, 21st May 1913 T. B. Felder Repudiates Report of Activity for Frank [Last Updated On: April 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 132 Thursday, 22nd May 1913 Grand Jury Wont Hear Leo Frank or Lee [Last Updated On: April 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 133 Friday, 23rd May 1913 Dictograph Record Used Against Felder [Last Updated On: April 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 134 Friday, 23rd May 1913 Felder Denies Phagan Bribe; Calls Colyar Crook and Liar [Last Updated On: April 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 135 Friday, 23rd May 1913 Felder Denies Phagan Bribery; Dictograph Record Used Against Felder [Last Updated On: April 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 136 Friday, 23rd May 1913 Frank Feeling Fine But Will Not Discuss His Case [Last Updated On: April 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 137 Friday, 23rd May 1913 Here is Affidavit Charging Bribery [Last Updated On: April 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 138 Friday, 23rd May 1913 Indictment of Both Lee and Frank is Asked [Last Updated On: April 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 139 Saturday, 24th May 1913 Beavers Says He Will Seek Indictments [Last Updated On: April 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 140 Saturday, 24th May 1913 Blease Ironic in Comments on Felder Trap [Last Updated On: April 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 141 Saturday, 24th May 1913 Colyar Called Convict and Insane [Last Updated On: April 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 142 Saturday, 24th May 1913 Colyar Held for Forgery [Last Updated On: April 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 143 Saturday, 24th May 1913 Dictograph Catches Mayor in Net [Last Updated On: April 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 144 Saturday, 24th May 1913 Dictograph Record Alleged Bribe Offer [Last Updated On: April 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 145 Saturday, 24th May 1913 Felder Charges Police Plot to Shield Slayer [Last Updated On: April 22nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 146 Saturday, 24th May 1913 Felders Fight is to Get Chief and Lanford Out of Office [Last Updated On: April 22nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 147 Saturday, 24th May 1913 Frame-Up Aimed at Burns Men, Says Tobie [Last Updated On: April 22nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 148 Saturday, 24th May 1913 Jones Attacks Beavers and Charges Police Crookedness [Last Updated On: April 22nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 149 Saturday, 24th May 1913 Mayor Admits Dictograph is Correct [Last Updated On: April 22nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 150 Saturday, 24th May 1913 Miles Says He Had Mayor Go to Room [Last Updated On: April 22nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 151 Saturday, 24th May 1913 Plot on Life of Beavers Told by Colyar [Last Updated On: April 22nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 152 Saturday, 24th May 1913 Strangulation Charge is in Indictments [Last Updated On: April 22nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 153 Sunday, 25th May 1913 Attorney, in Long Statement, Claims Dictograph Records Against Him Padded [Last Updated On: April 22nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 154 Sunday, 25th May 1913 Colyar Arrest Proper End to Plot of Crook [Last Updated On: April 22nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 155 Sunday, 25th May 1913 Colyar, Held as Forger, is Freed on Bond; Long Crime Record Charged [Last Updated On: April 22nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 156 Sunday, 25th May 1913 Dorsey to Present Graft Charges if They Stand Up [Last Updated On: April 22nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 157 Sunday, 25th May 1913 Ill Indict Gang, Says Beavers [Last Updated On: April 22nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 158 Sunday, 25th May 1913 Long Criminal Record of Colyar is Cited [Last Updated On: April 22nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 159 Monday, 26th May 1913 Accuses Tobie of Kidnaping Attempt [Last Updated On: April 22nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 160 Monday, 26th May 1913 Evidence Against Frank Conclusive, Say Police [Last Updated On: April 22nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 161 Monday, 26th May 1913 Lay Bribery Effort to Franks Friends [Last Updated On: April 22nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 162 Monday, 26th May 1913 Mason Blocks Attempt to Oust Chief [Last Updated On: April 22nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 163 Monday, 26th May 1913 Mayor Eager to Bring Back Tenderloin, Declares Chief [Last Updated On: April 22nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 164 Monday, 26th May 1913 Mayor Gives Out Sizzling Reply to Chief Beavers [Last Updated On: April 22nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 165 Monday, 26th May 1913 Pinkerton Man Says Frank is Guilty [Last Updated On: April 22nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 166 Monday, 26th May 1913 Will Take Charge of Graft to Grand Jury for Vindication [Last Updated On: April 22nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 167 Tuesday, 27th May 1913 Burns Man Quits Case; Declares He Is Opposed [Last Updated On: April 22nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 168 Tuesday, 27th May 1913 Felder Aide Offers Vice List to Chief [Last Updated On: April 22nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 169 Tuesday, 27th May 1913 State Faces Big Task in Trial of Frank as Slayer [Last Updated On: April 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 170 Tuesday, 27th May 1913 Suspicion Turned to Conley; Accused by Factory Foreman [Last Updated On: April 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 171 Wednesday, 28th May 1913 Chief Beavers to Renew His Vice War [Last Updated On: April 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 172 Wednesday, 28th May 1913 Conley Says Frank Took Him to Plant on Day of Slaying [Last Updated On: April 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 173 Wednesday, 28th May 1913 Conley Was in Factory on Day of Slaying [Last Updated On: April 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 174 Wednesday, 28th May 1913 Woman Writes in Defense of Leo M. Frank [Last Updated On: April 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 175 Thursday, 29th May 1913 Burns Joins in Hunt for Phagan Slayer [Last Updated On: April 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 176 Thursday, 29th May 1913 Conley Re-enacts in Plant Part He Says He Took in Slaying [Last Updated On: April 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 177 Thursday, 29th May 1913 Felder Bribery Charge Expected [Last Updated On: April 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 178 Thursday, 29th May 1913 Negro Conleys Affidavit Lays Bare Slaying [Last Updated On: April 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 179 Thursday, 29th May 1913 Ready to Indict Conley as an Accomplice [Last Updated On: April 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 180 Friday, 30th May 1913 Negro Conley Now Says He Helped to Carry Away Body [Last Updated On: April 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 181 Saturday, 31st May 1913 Conley Star Actor in Dramatic Third Degree [Last Updated On: April 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 182 Saturday, 31st May 1913 Plan to Confront Conley and Frank for New Admission [Last Updated On: April 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 183 Saturday, 31st May 1913 Silence of Conley Put to End by Georgian [Last Updated On: April 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 184 Saturday, 31st May 1913 Special Session of Grand Jury Called [Last Updated On: April 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 185 Sunday, 1st June 1913 Confession of Conley Makes No Changes in States Case [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 186 Sunday, 1st June 1913 Conley is Unwittingly Friend of Frank, Says Old Police Reporter [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 187 Sunday, 1st June 1913 Conleys Story Cinches Case Against Frank, Says Lanford [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 188 Sunday, 1st June 1913 Dorseys Grill Fails to Make Conley Admit Hand in Killing [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 189 Sunday, 1st June 1913 Today is Mary Phagans Birthday; Mother Tells of Party She Planned [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 190 Monday, 2nd June 1913 5 to Testify Frank Was at Home at Hour Negro Says He Aided [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 191 Monday, 2nd June 1913 Beavers to Talk Over the Felder Row With Dorsey [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 192 Monday, 2nd June 1913 Negro Cook at Home Where Frank Lived Held by the Police [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 193 Tuesday, 3rd June 1913 Bitter Fight Certain in Trial of Frank [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 194 Tuesday, 3rd June 1913 Felder Says He Will Lay Bare Startling Police Graft Plans [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 195 Wednesday, 4th June 1913 Cooks Sensational Affidavit [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 196 Wednesday, 4th June 1913 Fain Named in Vice Quiz as Resort Visitor [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 197 Wednesday, 4th June 1913 Franks Cook Was Counted Upon as Defense Witness [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 198 Thursday, 5th June 1913 Challenges Felder to Prove His Charge [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 199 Thursday, 5th June 1913 Cook Repudiates Entire Affidavit Police Possess [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 200 Thursday, 5th June 1913 I Know My Husband is Innocent, Asserts Wife of Leo M. Frank [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 201 Thursday, 5th June 1913 Mother Here to Aid Frank in Trial [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 202 Thursday, 5th June 1913 New Conley Confession Reported to Jury [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 203 Friday, 6th June 1913 Chief Says Law Balks His War on Vice [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 204 Friday, 6th June 1913 Report Negro Found Who Saw Phagan Attack [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 205 Saturday, 7th June 1913 Defense Bends Efforts to Prove Conley Slayer [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 206 Saturday, 7th June 1913 Defense Digs Deep to Show Conley is Phagan Girl Slayer [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 207 Saturday, 7th June 1913 Mrs. Frank Attacks Solicitor H. M. Dorsey in a New Statement [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 208 Sunday, 8th June 1913 Fair Play Alone Can Find Truth in Phagan Puzzle, Declares Old Reporter [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 209 Monday, 9th June 1913 Foreman Tells Why He Holds Conley Guilty [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 210 Monday, 9th June 1913 Rosser Asks Grand Jury Grill for Conley [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 211 Tuesday, 10th June 1913 Eyewitness to Phagan Slaying Sought [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 212 Tuesday, 10th June 1913 Indictment of Felder and Fain Asked [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 213 Wednesday, 11th June 1913 Asks Beavers to Investigate Affidavit [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 214 Wednesday, 11th June 1913 Felder Returns Phagan Fund to Givers [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 215 Wednesday, 11th June 1913 Plot Exposed, Says Felder, But Lanford Doubts Affidavit [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 216 Wednesday, 11th June 1913 Police Hold Conley By Courts Order [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 217 Thursday, 12th June 1913 Face Conley and Frank, Lanford Urges [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 218 Friday, 13th June 1913 Judge Roan to Decide Conleys Jail Fate [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 219 Friday, 13th June 1913 Negro Freed But Jailed Again On Suspicion [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 220 Saturday, 14th June 1913 Sheriff Mangum Near End, Says Lawyer Smith [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 221 Saturday, 14th June 1913 State Takes Advantage of Points Known [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 222 Monday, 16th June 1913 Colyar Returns Promising Sensation [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 223 Monday, 16th June 1913 Dorsey Aide Says Frank Is Fast In Net [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 224 Tuesday, 17th June 1913 Sensations in Phagan Case at Hand [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 225 Wednesday, 18th June 1913 Rush Plans for Trial of Leo Frank [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 226 Thursday, 19th June 1913 Blow Aimed at Formby Story [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 227 Friday, 20th June 1913 Frank Trial Will Not Be Long One [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 228 Saturday, 21st June 1913 Justice Aim in Phagan Case, Says Hooper [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 229 Sunday, 22nd June 1913 Arnold to Aid Frank [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 230 Sunday, 22nd June 1913 Jurors, Not Newspapers, To Return Frank Verdict, Declares Old Reporter [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 231 Monday, 23rd June 1913 State Ready for Frank Trial on June 30 [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 232 Monday, 23rd June 1913 Venire of 72 for Frank Jury Is Drawn [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 233 Tuesday, 24th June 1913 Both Sides Called in Conference by Judge; Trial Set for July 28 [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 234 Wednesday, 25th June 1913 Conley, Put on Grill, Sticks Story [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 235 Thursday, 26th June 1913 Stover Girl Will Star in Frank Trial [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 236 Friday, 27th June 1913 Lanford and Felder Are Held for Libel [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 237 Friday, 27th June 1913 New Frank Evidence Held by Dorsey [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 238 Saturday, 28th June 1913 Gov. Slaton Takes Oath Simply [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 239 Saturday, 28th June 1913 State Secures New Phagan Evidence [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 240 Sunday, 29th June 1913 Brilliant Legal Battle Is Sure as Hooper And Arnold Clash in Trial of Leo Frank [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 241 Sunday, 29th June 1913 Many Experts to Take Stand in Frank Trial [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 242 Monday, 30th June 1913 Conley Tale Is Hope of Defense [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 243 Tuesday, 1st July 1913 Colyar Indicted as Libeler of Col. Felder [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 244 Tuesday, 1st July 1913 Colyar Not Indicted On Charge of Libel [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 245 Tuesday, 1st July 1913 Frank Is Willing for State to Grill Him [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 246 Tuesday, 1st July 1913 May Indict Conley as Slayer [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 247 Tuesday, 1st July 1913 May Indict Conley in Phagan Case [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 248 Tuesday, 1st July 1913 “No” Bill Is Returned Against A. S. Colyar [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 249 Wednesday, 2nd July 1913 Findings in Probe are Guarded [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 250 Thursday, 3rd July 1913 Attempt by Colyar To Disbar Felder Is Halted; Tries Again [Last Updated On: May 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 251 Thursday, 3rd July 1913 Writ Sought In Move to Free Negro Lee [Last Updated On: June 15th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 252 Friday, 4th July 1913 New Testimony Lays Crime to Conley [Last Updated On: June 15th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 253 Saturday, 5th July 1913 Application for Lee’s Release Delayed [Last Updated On: June 15th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 254 Saturday, 5th July 1913 Drop Ninth in Police Scandal [Last Updated On: June 15th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 255 Saturday, 5th July 1913 Liberty for Newt Lee Sought [Last Updated On: June 15th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 256 Saturday, 5th July 1913 Unbiased in the Flanders Case, Says Slaton [Last Updated On: June 15th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 257 Sunday, 6th July 1913 Application to Release Lee is Ready to File [Last Updated On: June 15th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 258 Sunday, 6th July 1913 New Move in Phagan Case by Solicitor [Last Updated On: June 15th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 259 Sunday, 6th July 1913 Phagan Case Centers on Conley; Negro Lone Hope of Both Sides [Last Updated On: June 15th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 260 Monday, 7th July 1913 Lee’s Attorney is Ready for Writ Fight [Last Updated On: June 15th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 261 Monday, 7th July 1913 Operations of Slavers in Hotels Bared [Last Updated On: June 15th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 262 Tuesday, 8th July 1913 Attitude of Defense Secret [Last Updated On: June 15th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 263 Tuesday, 8th July 1913 Girl Tells of Life in Slavers’ Hands [Last Updated On: June 15th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 264 Tuesday, 8th July 1913 Grants Right to Demand Lee’s Freedom [Last Updated On: June 15th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 265 Tuesday, 8th July 1913 Police Hunt Principals in Expose [Last Updated On: June 15th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 266 Tuesday, 8th July 1913 Refused by Brown, Mangham Now Asks Slaton for Pardon [Last Updated On: June 15th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 267 Tuesday, 8th July 1913 State Sure Lee Will Not Be Released [Last Updated On: June 15th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 268 Wednesday, 9th July 1913 Girl Springs Sensation in Phagan Case [Last Updated On: June 15th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 269 Wednesday, 9th July 1913 New Evidence in Phagan Case Found [Last Updated On: June 15th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 270 Wednesday, 9th July 1913 Sensations in Story of Girl Victim [Last Updated On: June 15th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 271 Thursday, 10th July 1913 Beavers in Speech Warns Policemen to Keep Out of Dives [Last Updated On: June 15th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 272 Thursday, 10th July 1913 Beavers’ War on Vice is Lauded by Women [Last Updated On: June 15th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 273 Thursday, 10th July 1913 Chief Expects Arrests in Vice Probe [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 274 Thursday, 10th July 1913 Says Conley Confessed Slaying [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 275 Friday, 11th July 1913 Girl Tells Police Startling Story of Vice Ring [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 276 Friday, 11th July 1913 Mincey’s Story Jolts Police to Activity [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 277 Friday, 11th July 1913 Slaying Charge for Conley Is Expected [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 278 Saturday, 12th July 1913 Conley Kept on Grill 4 Hours [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 279 Saturday, 12th July 1913 Dragnet for ‘Slavers’ Is Set [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 280 Saturday, 12th July 1913 Five Caught in Beavers’ Vice Net [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 281 Saturday, 12th July 1913 Parents Are Blamed for ‘Slavery’ [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 282 Saturday, 12th July 1913 Says Women Heard Conley Confession [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 283 Sunday, 13th July 1913 Affidavits to Back Mincey Story Found [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 284 Sunday, 13th July 1913 Indictment of Conley Puzzle for Grand Jury [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 285 Sunday, 13th July 1913 Seek Negro Who Says He Was Eye-Witness to Phagan Murder [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 286 Monday, 14th July 1913 Girl Bares New Vice System [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 287 Monday, 14th July 1913 Mincey’s Own Story [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 288 Monday, 14th July 1913 Prosecution Attacks Mincey’s Affidavit [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 289 Monday, 14th July 1913 Vice Pickets Posted at Hotels [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 290 Tuesday, 15th July 1913 Holloway Corroborates Mincey’s Affidavit [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 291 Tuesday, 15th July 1913, Atlanta Police Close 2 Rooming Houses, The Atlanta Georgian [Last Updated On: July 3rd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 292 Tuesday, 15th July 1913 White Men Fined in War on Negro Dives [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 293 Tuesday, 15th July 1913 Woodward Aids Chief in Vice Crusade [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 294 Wednesday, 16th July 1913 Dorsey Adds Startling Evidence [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 295 Wednesday, 16th July 1913 State to Fight Move to Indict Jim Conley [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 296 Thursday, 17th July 1913 Dorsey Blocked Indictment of Conley [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 297 Thursday, 17th July 1913 Mayor and Broyles in War of Words [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 298 Thursday, 17th July 1913 Mayor Asked to Probe Action of Police [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 299 Thursday, 17th July 1913 Woodward Enemy to Society, Says Recorder Broyles [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 300 Thursday, 17th July 1913 Youth Accused in Vice Ring on Trial [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 301 Friday, 18th July 1913 Detectives Working to Discredit Mincey [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 302 Friday, 18th July 1913 Woodward-Broyles Breach Widens [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 303 Saturday, 19th July 1913 Dorsey Resists Move to Indict Jim Conley [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 304 Saturday, 19th July 1913 Natural Crank, Mayor’s Shot at Broyles [Last Updated On: July 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 305 Sunday, 20th July 1913 Attorney for Conley Makes a Statement [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 306 Sunday, 20th July 1913 Counsel of Frank Says Dorsey Has Sought to Hide Facts [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 307 Sunday, 20th July 1913 Dorsey Fights Movement to Indict Conley [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 308 Sunday, 20th July 1913 Mincey Ready to Tell Story to Grand Jury [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 309 Sunday, 20th July 1913 Mincey Story Declared Vital To Both Sides in Frank Case [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 310 Monday, 21st July 1913 Doctor And Girl Are Taken On Vice Charge [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 311 Monday, 21st July 1913 Four Women Caught In Vice Net Escape From Martha Home [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 312 Monday, 21st July 1913 Grand Jury Meets to Consider Conley Case [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 313 Monday, 21st July 1913 Protest of Solicitor Dorsey Wins [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 314 Tuesday, 22nd July 1913 Defense Asks Ruling on Delaying Frank Trial [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 315 Tuesday, 22nd July 1913 Grand Jury Defers Action on Conley [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 316 Tuesday, 22nd July 1913 Story of Phagan Case by Chapters [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 317 Wednesday, 23rd July 1913 Conley is Confronted with Lee Dorsey Grills Negroes in Same Cell at Jail [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 318 Wednesday, 23rd July 1913 Lanford Ridicules Bludgeon Evidence [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 319 Wednesday, 23rd July 1913 Second Chapter in Phagan Mystery [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 320 Thursday, 24th July 1913 Frank Trial Delay up to Roan [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 321 Thursday, 24th July 1913 Let the Frank Trial Go On [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 322 Thursday, 24th July 1913 Third Chapter in Phagan Mystery [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 323 Thursday, 24th July 1913 Veneir is Drawn to Try Leo M. Frank Monday [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 324 Friday, 25th July 1913 Witnesses for Frank Called [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 325 Saturday, 26th July 1913 Chapter 5 in Phagan Case [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 326 Saturday, 26th July 1913 Pinkerton Chief Scored by Lanford [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 327 Saturday, 26th July 1913 Present New Evidence Against Frank [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 328 Sunday, 27th July 1913 Brewster Denies Aiding Dorsey in Phagan Case [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 329 Sunday, 27th July 1913 Defense Claims Conley and Lee Prepared Notes [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 330 Sunday, 27th July 1913 Every Bit of Evidence Against Frank Sifted and Tested, Declares Solicitor [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 331 Sunday, 27th July 1913 Frank Fights for Life Monday [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 332 Sunday, 27th July 1913 Frank Watches Closely as the Men Who are to Decide Fate are Picked [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 333 Sunday, 27th July 1913 Phagan Case of Peculiar And Enthralling Interest [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 334 Sunday, 27th July 1913 Pinkerton Men Brand Lanford Charges False [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 335 Sunday, 27th July 1913 Prominent Atlantans Named On Frank Trial Jury Venire [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 336 Sunday, 27th July 1913 Public Demands Frank Trial To-morrow [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 337 Sunday, 27th July 1913 State Bolsters Conley [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 338 Sunday, 27th July 1913 Trial to Surpass in Interest Any in Fulton County History [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 339 Sunday, 27th July 1913 Venire Whipped Into Shape Rapidly; Negro Is Eligible [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 340 Sunday, 27th July 1913 Work of Choosing Jury for Trial of Frank Difficult [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 341 Monday, 28th July 1913 Frank, Feeling Tiptop, Smiling and Confident, is Up Long Before Trial [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 342 Monday, 28th July 1913 Frank Jury [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 343 Monday, 28th July 1913 Jury Complete to Try Frank [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 344 Monday, 28th July 1913 Mary Phagan’s Mother Testifies [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 345 Tuesday, 29th July 1913 After Rosser’s Fierce Grilling All Negro, Newt Lee, Asked for Was Chew or Bacca-AnyKind [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 346 Tuesday, 29th July 1913 Defense Wins Point After Fierce Lawyers’ Clash [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 347 Tuesday, 29th July 1913 Lee’s Quaint Answers Rob Leo Frank’s Trial of All Signs of Rancor [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 348 Tuesday, 29th July 1913 Tragedy, Ages Old, Lurks in Commonplace Court Setting [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 349 Wednesday, 30th July 1913 Defense Plans Sensation, Line of Queries Indicates [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 350 Wednesday, 30th July 1913 Flashes of Tragedy Pierce Legal Tilts at Frank Trial [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 351 Wednesday, 30th July 1913 Frank’s Mother Pitiful Figure of the Trial [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 352 Wednesday, 30th July 1913 Gantt Has Startling Evidence; Dorsey Promises New Testimony Against Frank [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 353 Wednesday, 30th July 1913 Rosser’s Examination of Lee Just a Shot in Dark; Hoped to Start Quarry [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 354 Thursday, 31st July 1913 Collapse of Testimony of Black and Hix Girl’s Story Big Aid to Frank [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 355 Thursday, 31st July 1913 Crimson Trail Leads Crowd to Courtroom Sidewalk [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 356 Thursday, 31st July 1913 Holloway Accused by Solicitor Dorsey of Entrapping State [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 357 Thursday, 31st July 1913 Red Bandanna, a Jackknife and Plennie Minor Preserve Order [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 358 Thursday, 31st July 1913 Scott Trapped Us, Dorsey Charges; Pinkerton Man Is Also Attacked by the Defense [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 359 Thursday, 31st July 1913 State Balloon Soars When Dorsey, Roiled, Cries ‘Plant’ [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 360 Friday, 1st August 1913 Conley Takes Stand Saturday [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 361 Friday, 1st August 1913 Defense Not Helped by Witnesses Accused of Entrapping the State [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 362 Friday, 1st August 1913 Dorsey Unafraid as He Faces Champions of the Atlanta Bar [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 363 Friday, 1st August 1913 Girl Slain After Frank Left Factory, Believed to be Defense Theory [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 364 Friday, 1st August 1913 Sherlocks, Lupins and Lecoqs See Frank Trial [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 365 Saturday, 2nd August 1913 Defense Threatens a Mistrial [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 366 Saturday, 2nd August 1913 Frank Juror’s Life One Grand, Sweet SongNot [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 367 Saturday, 2nd August 1913 Roan Holding Scales of Justice With Steady Hand [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 368 Saturday, 2nd August 1913 State Hopes Dr. Harris Fixed Fact That Frank Had Chance to Kill Girl [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 369 Saturday, 2nd August 1913 Will 5 Ounces of Cabbage Help Convict Leo M. Frank? [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 370 Sunday, 3rd August 1913 Conley to Bring Frank Case Crisis [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 371 Sunday, 3rd August 1913 First Week of Frank Trial Ends With Both Sides Sure of Victory [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 372 Sunday, 3rd August 1913 Leo Frank’s Eyes Show Intense Interest in Every Phase of Case [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 373 Monday, 4th August 1913 Boiled Cabbage Brings Hypothetical Question Stage in Frank’s Trial [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 374 Monday, 4th August 1913 Conley’s Story In Detail; Women Barred By Judge [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 375 Monday, 4th August 1913 Dorsey Tries to Prove Frank Had Chance to Kill Girl [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 376 Monday, 4th August 1913 Dramatic Moment of Trial Comes as Negro Takes Stand [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 377 Monday, 4th August 1913 Envy Not the Juror! His Lot, Mostly, Is Monotony [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 378 Monday, 4th August 1913 Frank Calm and Jurors Tense While Jim Conley Tells His Ghastly Tale [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 379 Monday, 4th August 1913 Frank Witness Nearly Killed By a Mad Dog [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 380 Monday, 4th August 1913 Jim Conley’s Story as Matter of Fact as if it Were of His Day’s Work [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 381 Monday, 4th August 1913 Jurors Strain Forward to Catch Conley Story; Frank’s Interest Mild [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 382 Monday, 4th August 1913 Ordeal is Borne with Reserve by Franks [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 383 Monday, 4th August 1913 Rosser’s Grilling of Negro Leads to Hot Clashes by Lawyers [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 384 Tuesday, 5th August 1913 Conleys Charge Turns Frank Trial Into Fight To Worse Than Death [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 385 Tuesday, 5th August 1913 Many Discrepancies To Be Bridged in Conleys Stories [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 386 Tuesday, 5th August 1913 Mrs. Frank Breaks Down in Court [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 387 Tuesday, 5th August 1913 Rosser Goes Fiercely After Jim Conley [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 388 Tuesday, 5th August 1913 Traditions of the South Upset; White Mans Life Hangs on Negros Word [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 389 Wednesday, 6th August 1913 Accuser of Conley is Ready to Testify [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 390 Wednesday, 6th August 1913 Can Jury Obey if Told to Forget Base Charge? [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 391 Wednesday, 6th August 1913 Conley Swears Frank Hid Purse [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 392 Wednesday, 6th August 1913 Crowd Set in Its Opinions [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 393 Wednesday, 6th August 1913 Dorsey Accomplishes Aim Despite Big Odds [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 394 Wednesday, 6th August 1913 Judge Will Rule on Evidence Attacked by Defense at 2 P.M. [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 395 Thursday, 7th August 1913 Jim Conley, the Ebony Chevalier of Crime, is Darktowns Own Hero [Last Updated On: July 30th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 396 Thursday, 7th August 1913 Roans Ruling Heavy Blow to Defense [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 397 Thursday, 7th August 1913 State Ends Case Against Frank [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 398 Thursday, 7th August 1913 Trial as Varied as Vaudeville Exhibition [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 399 Thursday, 7th August 1913 Trial Experts Conflict on Time of Girls Death [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 400 Friday, 8th August 1913 Bits of Circumstantial Evidence, as Viewed by State, Strands in Rope [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 401 Friday, 8th August 1913 Scott Put Conleys Story in Strange Light [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 402 Friday, 8th August 1913 State, Tied by Conleys Story, Now Must Stand Still Under Hot Fire [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 403 Friday, 8th August 1913 Witnesses Attack Conley Story [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 404 Saturday, 9th August 1913 Absence of Alienists and the Hypothetical Question Distinguishes Frank Trial [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 405 Saturday, 9th August 1913 Confusion of Holloway Spoils Close of Good Day for the Defense [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 406 Saturday, 9th August 1913 Daltons Testimony False, Girl Named on Stand Says [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 407 Saturday, 9th August 1913 Exposure of Conley Story Time Flaws is Sought by Defense [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 408 Saturday, 9th August 1913 Heres the Time Clock Puzzle in Frank Trial; Can You Figure It Out? [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 409 Saturday, 9th August 1913 State Attacks Frank Report [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 410 Sunday, 10th August 1913 Case Never is Discussed by Frank Jurors [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 411 Sunday, 10th August 1913 Conley, Unconcerned, Asks Nothing of Trial [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 412 Sunday, 10th August 1913 Dalton Sticks Firmly To Story Told on Stand [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 413 Sunday, 10th August 1913 Frank or Conley? Still Question [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 414 Sunday, 10th August 1913 Frank Struggles to Prove His Conduct Was Blameless [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 415 Sunday, 10th August 1913 Interest in Trial Now Centers in Story of Mincey [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 416 Sunday, 10th August 1913 Mary Phagans Mother to be Spared at Trial [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 417 Sunday, 10th August 1913 One Glance at Conley Boosts Darwin Theory [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 418 Sunday, 10th August 1913 Phagan Trial Makes Eleven Widows But Jurors Wives Are Peeresses Also [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 419 Sunday, 10th August 1913 Study of Frank Convicts, Then It Turns and Acquits [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 420 Monday, 11th August 1913 Defense Bitterly Attacks Harris [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 421 Monday, 11th August 1913 Deputy Hunting Scalp Of Juror-Ventiloquist [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 422 Monday, 11th August 1913 Grief-Stricken Mother Shows No Vengefulness [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 423 Monday, 11th August 1913 Interest Unabated as Dramatic Frank Trial Enters Third Week [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 424 Tuesday, 12th August 1913 Attacks on Dr. Harris Give Defense Good Day [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 425 Tuesday, 12th August 1913 Frank Trial Witness is Sure, At Least, of One Thinga Good Ragging [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 426 Tuesday, 12th August 1913 Peoples Cry for Justice Is Proof Sentiment Still Lives [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 427 Tuesday, 12th August 1913 State Charges Premeditated Crime [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 428 Wednesday, 13th August 1913 Both Sides Aim for Justice in the Trial of Frank [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 429 Wednesday, 13th August 1913 Franks Mother Stirs Courtroom [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 430 Wednesday, 13th August 1913 State Calls More Witnesses; Defense Builds Up an Alibi [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 431 Thursday, 14th August 1913 State Fights Franks Alibi [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 432 Thursday, 14th August 1913 State Wants Wife and Mother Excluded [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 433 Thursday, 14th August 1913 States Sole Aim is to Convict, Defenses to Clear in Modern Trial [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 434 Thursday, 14th August 1913 Steel Workers Enthralled by Leo Frank Trial [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 435 Friday, 15th August 1913 Frank Prepares to Take Stand [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 436 Friday, 15th August 1913 Testimony of Girls Help to Leo M. Frank [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 437 Friday, 15th August 1913 What They Say Wont Hurt Leo Frank; State Must Prove Depravity [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 438 Saturday, 16th August 1913 Girls Testify For and Against Frank [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 439 Saturday, 16th August 1913 Many Testify to Franks Good Character [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 440 Saturday, 16th August 1913 Mothers Love Gives Trial Its Great Scene [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 441 Saturday, 16th August 1913 Statement by Frank Will Be the Climactic Feature of the Trial [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 442 Sunday, 17th August 1913 Supreme Test Comes As State Trains Guns On Frank's Character [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 443 Monday, 18th August 1913 Leo Frank Testifies [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 444 Tuesday, 19th August 1913 Jim Conley To Be Recalled [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 445 Wednesday, 20th August 1913 State Closes Frank Case Near Jury Defense Begins Its Sur-rubettual. Hopes To Conclude Quickly [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 446 Thursday, 21st August 1913 Mass Of Perjuries Charged By Arnold Centers Hot Attack On Conley. Ridicules Prosecution Theory [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 447 Friday, 22nd August 1913 Rosser Begins Final Plea [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 448 Sunday, 24th August 1913 Dorsey Demands Death Penalty For Frank In Thrilling Closing Plea [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]

- 449 Monday, 25th August 1913 Frank Case To Jury Today Leo, Frank On His Way From Jail To Court [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2023] [Originally Added On: December 1st, 2023]